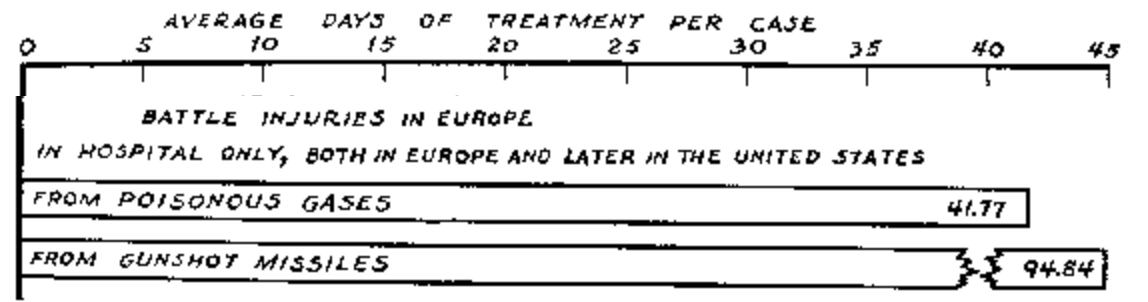

There is a relationship between war (and death) and counting things.1 Some of the best known data visualizations pertain to the casualties of war (e.g. Florence Nightingale’s coxcomb chart, Diagram of the Causes of Mortality, 1858).

When I came upon Lt. Colonel Albert G. Love’s 1931 “War Casualties”2 my curiosity was piqued. Focused on “the World War” (at that date there had only been one), Colonel Love describes his task in the preface:

An attempt is made in the following pages to outline a system for estimating, on the basis of our casualty experience in past wars, the requirements for medical service including hospitalization and evacuation of front line casualties; and further to show how intimately the question of replacements for all branches of an army is related to casualty rates, and also to prompt and efficient medical care.

Love’s goal is not ignoble, and there’s something oddly charming about visualizations made by hand — annotations and all, which made it (briefly) easy to ignore the meaning behind the charts.

Take Figure 56, for example: Loss of manpower from war (poisonous) gases in the Theater of Operations, during successive months (below).

Or Figure 48, for another: Theater of Operations war gas cases disposed of in the Zone of the Interior by return to duty, death, or disability discharge when sent to the Zone of the Interior for further treatment.

It’s particularly striking that the category “disposed of” encompasses: return to duty, disability discharge, and death, which seem like very different outcomes.

I’ve chosen “War Gas” examples because of Wilfred Owen’s 1921 poem on one such casualty, Dulce et Decorum Est, which has stuck with me ever since we read it in history class when I was 16.

Dulce et Decorum Est

by Wilfred OwenBent double, like old beggars under sacks,

Knock-kneed, coughing like hags, we cursed through sludge,

Till on the haunting flares we turned our backs,

And towards our distant rest began to trudge.

Men marched asleep. Many had lost their boots,

But limped on, blood-shod. All went lame; all blind;

Drunk with fatigue; deaf even to the hoots

Of gas-shells dropping softly behind.Gas! GAS! Quick, boys!—An ecstasy of fumbling

Fitting the clumsy helmets just in time,

But someone still was yelling out and stumbling

And flound’ring like a man in fire or lime.—

Dim through the misty panes and thick green light,

As under a green sea, I saw him drowning.In all my dreams before my helpless sight,

If in some smothering dreams, you too could pace

He plunges at me, guttering, choking, drowning.

Behind the wagon that we flung him in,

And watch the white eyes writhing in his face,

His hanging face, like a devil’s sick of sin;

If you could hear, at every jolt, the blood

Come gargling from the froth-corrupted lungs,

Obscene as cancer, bitter as the cud

Of vile, incurable sores on innocent tongues,—

My friend, you would not tell with such high zest

To children ardent for some desperate glory,

The old Lie: Dulce et decorum est

Pro patria mori.

Neither the numbers nor their graphical depictions glorify war, but there is something immeasurable caught in Owen’s poem, and the juxtaposition of the two brought to mind a Stalin aphorism:3

When one man dies it’s a tragedy. When thousands die it’s statistics.